By: Sarah Gallen

Abstract:

This study investigates the genetic and environmental mechanisms that regulate wing dimorphism in pea aphids, focusing on the expression of follistatin gene paralogs (FS1, FS2, FS3) in the brains of winged and wingless male and female aphids. Using in-situ hybridization probes, brain scans revealed that FS1 and FS3 are co-expressed in the same neural domains, particularly in neurosecretory cells and glial progenitor regions. This overlap was more pronounced in wingless males. However, in wingless females, the scans revealed that FS1 and FS2 are coexpressed in the same brain region, with a brighter signal due to probes targeting both transcripts. These findings demonstrate the importance of gene expression in shaping adaptive morphological traits in response to environmental pressures.

Intro:

This experiment investigates the genetic and environmental mechanisms that regulate wing dimorphism in pea aphids (Acyrthosiphon pisum), focusing on the expression of the follistatin gene in the brains of male and female winged and wingless aphids. Aphids exhibit two morphs: winged (alate) and wingless (apterous). The winged morphs are adapted for dispersal, possessing full wings and sensory and reproductive adaptations for flight and colonization of new environments. The wingless morphs are optimized for reproduction, exhibiting higher fecundity but limited dispersal capability. This wing dimorphism allows these insects to balance the trade-offs between dispersal and reproduction, enhancing their adaptability to changing environments and resource availability. Gene duplication is believed to have contributed to the complexity of genetic regulation behind wing dimorphisms in aphids.

As the aphids develop, the nervous system processes sensory information and controls behavior. The brain, as the central part of the nervous system, integrates environmental cues and controls physiological responses. The nervous system also coordinates behavior through interactions with the endocrine system. Neurosecretory cells in the brain and other neural tissues play a crucial role by producing hormones that regulate growth, reproduction, and development. These cells act as a bridge between the nervous and endocrine systems, translating environmental cues into hormonal signals that influence physiological changes via gene expression.

Specifically, follistatin is a hormone produced in several forms. These follistatin paralogs–fs-1, fs-2, and fs-3—are critical determinants of wing morphology in male and female aphids. The divergence in the expression of these paralogs suggests that gene duplication has allowed aphids to balance the expression of traits beneficial for either dispersal or reproduction based on environmental cues. These studies indicate that fs genes are all slightly different versions of an original gene, with each paralog evolving to take on specific roles in regulating wing morphology. There is abundant evidence from studies that suggest follistatin genes have evolved through gene duplication, leading to the formation of distinct paralogs.

By studying brain scans and the expression of follistatin paralogs, this research aims to uncover how gene expression regulates wing dimorphisms across the sexes. Specifically, it aims to understand how genetic regulation in neural tissues influences aphids, enhancing the understanding of adaptive mechanisms in response to environmental pressures. The experiment hypothesizes that follistatin paralogs show differential expression in the brains of winged versus wingless aphids, depending on the sex, and that these expression patterns contribute to regulating wing morphology.

Materials and Methods:

Total RNA was collected from asexual females or wingless male nymphs using Trizol-chloroform extraction. Next, cDNA was generated from polyA+ RNA using SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase with oligo-dT primers followed by RNaseH digestion. For each follistatin paralog (1-3), cDNA clones were obtained by designing forward primers in the 5′ UTR and reverse primers in the 3′ UTR of each gene. Whole follistatin coding sequences and partial UTRs were amplified from cDNA with Phusion High-Fidelity 2x PCR Master Mix, cloned into pCR4-TOPO, and verified via Sanger sequencing. Additional primers were designed to amplify sequences from the second and third exons of fs2 or fs3, with the T7 promoter sequence included in the reverse primer to generate probe templates. Probe templates were again amplified with Phusion 2x Master Mix, purified with the Qiagen PCR purification kit. Probe synthesis was carried out using T7 RNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher) and DIG RNA labelling mix (Roche). Probes were then isolated via DNase treatment and Lithium-Chloride precipitation.

Asexual female and sexual male pea aphids were reared and collected as previously described (Saleh Ziabari et al., 2025)([https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2420893122]). First, second, and third instar nymphs were fixed overnight at 4C in 5% DMSO 1X PBS 6% Formaldehyde. Brains were dissected the following day in ice-cold 1X PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100 (0.1% PBT) and then quickly dehydrated in ice-cold 100% methanol. Brains were rehydrated in 1X PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 (0.1% PBTW) and treated with Proteinase K in 1X PBS at 4 degrees Celsius for 1 hr. Following four washes in PBTW, fluorescent in situ hybridization was carried out as previously described (attached references) except that we used SigmaFast Fast Red Tablets (Sigma Aldrich) instead of Thermo Fisher Fast Red substrate. Stained brains were mounted in 70% Glycerol on slides sealed with clear nail polish and imaged on a Leica SP6 scanning laser confocal microscope. Images were rendered in Imaris Viewer (10.0.0.1) and figures compiled in Adobe Photoshop (24.5.0).

Analysis and Discussion:

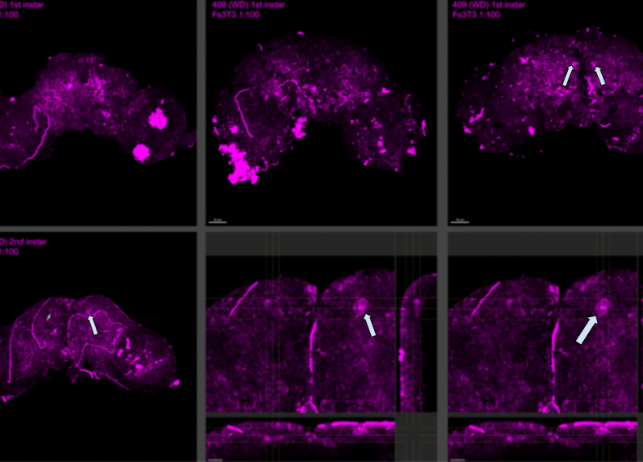

Neurosecretory cells are specialized neurons that release peptides, functioning as hormones, directly into the bloodstream to circulate throughout the body (definitions go in the intro). Using an in situ hybridization (hybridization happening in the same place where the gene is expressed as opposed to on the gel) probe specific to FS3 mRNA, cells were labeled and stained to visualize their fluorescence. Interestingly, FS3 probes also stained areas expressing FS1 despite sample 412 showing no FS3 expression. This overlap suggests that FS1 and FS3 are co-expressed within the same brain domains, potentially in neurosecretory cells. Further investigation using the probe to target neuropeptides, such as the ion transport peptide (ITP), highlighted large neurosecretory cells with fluorescence consistent with FS1 and FS3 expression. While this indicates a possible link between ITP and FS1/FS3 expression, it does not serve as definitive proof. Notably, wingless males exhibited no ITP expression, raising intriguing questions about its role and regulation in these cells.

The overlap in FS1 and FS3 expression in these neurosecretory cells suggests they may work together to influence wing development in male aphids. The absence of ITP in wingless males points to potential differences in genetic regulation tied to wing formation. These findings suggest that certain gene expression in neural tissues plays an important role in shaping adaptive wing traits in response to environmental pressures.

In multiple brains of 409 wingless samples, staining with the FS3-specific in situ hybridization probe revealed a noticeable difference in brightness compared to winged samples. This increased brightness in wingless brains is likely due to the probe targeting both FS1 and FS3 transcripts, whereas in winged samples, the probe only targets FS1. This dual staining in 409 suggests that FS1 and FS3 are co-expressed within the same brain domain. The expression follows a distinct pattern through the optic lobes, aligning with areas associated with glial progenitors, while the front and top regions correspond to neurosecretory cells. These glial progenitor cells are immature cells in the brain and spinal cord that can develop into different glial cells, which support and protect neurons. These cells play a key role in brain development and repair. The increased probe signal in 409 samples highlights the overlap in FS1 and FS3 expression, resulting in a doubling of transcript detection compared to winged counterparts.

As stated before, in wingless aphids, both FS1 and FS3 genes are active in the same brain regions. This overlapping activity causes a brighter signal in the brain scans of wingless aphids compared to winged ones, where only FS1 is active. This difference in gene activity aligns with specific areas of the brain. For example, FS1 and FS3 activity is found in regions tied to glial progenitor cells and neurosecretory cells. These brain regions are likely where important decisions regarding wing development are happening. Ultimately, the brain’s genetic activity influences whether aphids grow wings, depending on their environment and sex. Our findings align with the findings of a study on Calliphora erythrocephala, whichsupports this research on aphid wing dimorphism by showing how neurosecretory cells regulate development through hormonal control. These cells influence ovarian growth in flies. Similarly, our study on aphids proposes that FS1 and FS3 expression in brains aligns with neurosecretory regions, suggesting a hormonal or genetic regulatory mechanism affecting wing formation. Both studies highlight the brain’s role in controlling key traits through gene expression and endocrine interactions, showing how insects adapt to environmental pressures.

The image displays two zoom levels of a first instar wingless female brain, oriented with the anterior (head) at the top and the optic lobes at the bottom. A distinct line of expression runs through the optic lobes, while the neurosecretory cells at the top of the brain exhibit brighter staining. This brighter signal is due to probes targeting both FS1 and FS2 transcripts, indicating their co-expression in these regions. Additionally, the pink fluorescence observed corresponds to expression in the glia, further highlighting the spatial differentiation of transcript expression in the brain’s structures. All we can say is that there is staining similar to winged/wingless males, so FS2 may be expressed in the same brain domain in WL females as fs1 in winged males and FS1/FS3 in wingless males.

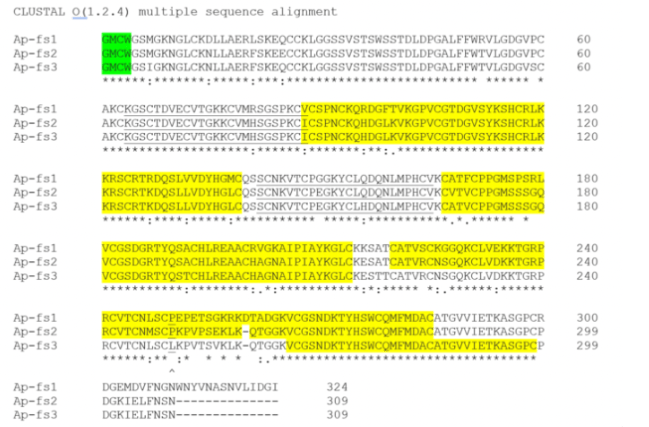

The cleavage site, a specific point where enzymes divide a protein into segments, serves as a reference point for understanding protein function and evolution. By aligning protein sequences after the cleavage site, regions of similarity that may indicate function or structural relationships can be identified. In this case, the Fs genes in three aphids show high similarity, suggesting that the change in role from development (fs1) to female environmentally induced winglessness (fs2) to genetically determined winglessness (fs3) is driven more by changes in gene regulation than by alterations in the protein sequences themselves. Highlighted regions in the alignment represent binding sites where neurosecretory cells can trigger intracellular processes. These findings suggest that while variations in protein sequences exist, they likely play a relatively minor role compared to regulatory changes in shaping the functional adaptations of aphids.

Conclusion:

Our research provides valuable insights into the genetic and environmental mechanisms regulating wing dimorphism in aphids, with a specific focus on the expression of follistatin paralogs in the brains of winged and wingless aphids across sexes. The overlap in FS1 and FS3 expression in wingless males and the presence of both FS1 and FS2 in female brains suggest that these paralogs play a critical role in determining wing morphology. These findings align with prior studies on Calliphora erythrocephala, reinforcing the idea that neurosecretory cells contribute to developmental regulation through hormonal control.

However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. One potential source of error lies in measuring the brightness of brain scan fluorescence, which can be subjective and dependent on imaging techniques. Therefore, the extent to which FS1, FS2, and FS3 expression directly impacts wing formation remains somewhat speculative. Future research should prioritize quantifying fluorescence brightness more objectively through digital image analysis tools that minimize human bias. By addressing these questions and refining current methodologies, future studies can build on the foundation established here, furthering the understanding of how generic regulation and environmental cues shape aphids and other insects.

The findings of a study on Calliphora erythrocephala support this research on aphid wing dimorphism by showing how neurosecretory cells regulate development through hormonal control. These cells influence ovarian growth in flies. Similarly, our study on aphids proposes that FS1 and FS3 expression in brains aligns with neurosecretory regions, suggesting a hormonal or genetic regulatory mechanism affecting wing formation. Both studies highlight the brain’s role in controlling key traits through gene expression and endocrine interactions, showing how insects adapt to environmental pressures.

Bibliography:

Biology, ecology, and management strategies for PEA aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in Pulse Crops | Journal of Integrated Pest Management | oxford academic. (n.d.-a). https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/11/1/18/5918920

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (n.d.). Animals & Nature. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/Animals-Nature

Functional significance of the neurosecretory brain cells and the Corpus Cardiacum in the female blow-fly, Calliphora Erythrocephala Meig | Journal of Experimental Biology | the company of Biologists. (n.d.-b). https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/29/1/137/12529/Functional-Significance-Of-The-Neurosecretory

Li, B., Bickel, R. D., Parker, B. J., Ziabari, O. S., Liu, F., Vellichirammal, N. N., Simon, J.-C., Stern, D. L., & Brisson, J. A. (2020, March 6). A large genomic insertion containing a duplicated follistatin gene is linked to the pea aphid male wing dimorphism. eLife. https://elifesciences.org/articles/50608

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—its evolution and adaptation | PNAS. (n.d.-c). https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1821201116

Leave a comment