By: Gabrielle Santema

Abstract:

Uterine Leiomyosarcoma (uLMS) is a rare, aggressive cancer with poor response to standard chemotherapies. The NOTCH pathway is an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway with oncogenic properties; when acting non-canonically/pathologically, it frequently activates the complementary Wnt/B-Catenin pathway. Both pathways rely on gamma-secretase to function properly. This prompted us to investigate the efficacy of gamma-secretase inhibitors in downregulating those downstream effectors involved in the development and metastasis of uLMS. Two uLMS cell lines, SK-LMS-1 (vulvar metastasis) and SK-UT-1B (uterine primary), were grown in media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Each cell line was then treated with MK-0752 or a combination therapy of MK-0752, gemcitabine, and docetaxel (MGD), and the expression of select genes (HES1 for NOTCH and C-Myc and Cyclin-D1 for Wnt/B-Catenin) was measured. Treatment efficacy was assessed using qPCR and Western Blots. qPCR results revealed a significant HES1 downregulation in SK-LMS-1 cells and a slighter one in SK-UT-1B cells when treated with MK-0752, indicating effective NOTCH pathway inhibition. MK-0752 and MGD treatments had varying efficacy in regulating C-Myc and Cyclin-D1 expression, indicating some (inconsistent) impact on the Wnt/B-Catenin pathway. Overall, SK-LMS-1 cells responded more favorably to treatments than did SK-UT-1B cells. Western blot analysis identified the present proteins as C-Myc and verified that MK-0752-treated samples had lower protein intensity and saturation than their control counterparts. This study demonstrates the potential of gamma-secretase inhibitors in targeting key signaling pathways of uLMS, thus suggesting their viability as an effective treatment for the malignancy.

Introduction:

Uterine Leiomyosarcoma (uLMS) is a rare and aggressive malignancy arising from smooth uterine muscle cells. It accounts for 65% of uterine sarcomas (Abedin et al., 2022). Current treatments of the disease depend on staging: early stages are generally treated via surgery, while advanced stages may use surgery in combination with common chemotherapies (including doxorubicin, gemcitabine, and docetaxel) (Abedin et al., 2022). Despite such treatment options, the five-year survival rate of patients with early-stage uLMS is under 50% and dro1ps to just 15% in advanced-stage patients (Abedin et al., 2022). uLMS also has exceptionally high recurrence rates, ranging, on average, from 50-70% (Abedin et al., 2024). The disease remains a challenge to diagnose and treat, as its symptoms (abnormal uterine bleeding, an enlarged uterus, and/or pelvic pressure) often mimic those of benign gynecological conditions (Abedin et al., 2022). Women’s health issues are also historically underdiagnosed, making it all the more challenging for those affected by uLMS to receive a timely diagnosis. Further, standard chemotherapy treatments frequently come with debilitating side effects, making it difficult for patients to consume effective doses (Abedin et al., 2024). Even at effective doses, studies have found that chemotherapy treatments do not lower recurrence rates to a statistically significant degree (Abedin et al., 2022). Thus, there exists a need for improved treatment options.

One promising but largely unexplored therapeutic strategy hinges on inhibiting the NOTCH signaling pathway. The NOTCH pathway is an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway that plays an oncogenic role in many cancers, including uLMS (Abedin et al., 2022). In the canonical pathway, a NOTCH ligand binds to a NOTCH receptor, triggering the release of Notch Intracellular Domain (NICD) via the action of gamma-secretase. The NICD translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a complex with DNA-binding transcription factors (like CSL/RBPjk) (Abedin et al., 2022). This ultimately results in the transcription of downstream effectors like HES1 (Abedin et al., 2022). Gamma secretase plays a critical role in the cleavage of the NOTCH receptor and consequently in the expression of downstream effectors. Thus, gamma-secretase inhibitors, such as DAPT and MK-0752, can be used to effectively block the NOTCH pathway (Abedin et al., 2022). The pathway can also act non-canonically. This will occur when a non-canonical NOTCH ligand binds to the receptor, thus triggering a signaling cascade independent of the usual transcription factors (Anderson, 2012). The non-canonical pathway is generally associated with pathological conditions. Such non-canonical activation can trigger several cellular responses; notably, it may activate other signaling pathways, including the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway (Anderson, 2012).

The Wnt/β-Catenin pathway is involved in several aspects of leiomyoma genesis (Sabeh, 2021). Studies have shown that selective overexpression of constitutively activated β-catenin in uterine mesenchyme during embryonic development — and in adults– gave rise to leiomyosarcoma-like tumors in the uterus of female mice (Tanwar, 2009). In the pathway, an extracellular Wnt ligand binds to a cell membrane receptor. This results in the formation of a multimeric protein complex, which promotes the dephosphorylation of β-Catenin. β-Catenin is thus able to accumulate in the nucleus and bind transcription factors, ultimately resulting in an increased expression of downstream target genes (like Cyclin D1 and C-MYC) (Sabeh, 2021). An over-accumulation of β-Catenin will result in over-expression of downstream effectors; this is primarily associated with pathological conditions (namely cancers like uLMS). Gamma-secretase inhibitors can prevent over-accumulation of β-Catenin by blocking the cleavage of E-cadherin (Sabeh, 2021). Given the Wnt/B-catenin pathway’s involvement in uLMS and its interactions with the NOTCH pathway, gamma-secretase inhibitors could effectively inhibit both pathways (Barat, 2017).

Considering the high recurrence rate, poor survival outcomes, and general inefficacy of existing uLMS treatments, it is evident that novel therapeutic techniques are necessary to combat the disease and improve patient outcomes. We aimed to determine whether directly targeting the NOTCH and Wnt/β-Catenin pathways with a gamma-secretase inhibitor might be an effective treatment plan. To test this hypothesis, uterine leiomyosarcoma cells were treated with the gamma-secretase inhibitor MK-0752 and a combination therapy of MK-0752, gemcitabine, and docetaxel (MGD), and the RNA and protein expression of their downstream effectors were measured.

Methods:

Cell treatment

Two cell lines were cultured to investigate this aim: SK-LMS-1, a vulvar metastasis from uterine leiomyosarcoma, and SK-UT-1B, a primary uterine leiomyosarcoma cell line with epithelial-like morphology. One line represents one patient, and thus, using two lines allows greater accuracy in results. Both cell lines were grown in media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Then, SK-LMS-1 and SK-UT-1B cells were serum starved for 4 hours and treated with either DMSO control, 1C30 concentration of MK-0752 alone, or in combination with gemcitabine and docetaxel (MGD) for 72 hours. 72 hours was chosen as the treatment time since this time frame was utilized in the lab’s most recent paper (Abedin et al., 2024). RNA extraction was then performed on the cells.

RNA extraction

To begin RNA extraction, 1×107 lysed cells were added to a petri dish. 600 ul of Buffer RLT Plus was added to the dish, and its contents were homogenized using a pipette. The homogenized lysate was then added to a gDNA Eliminator spin column placed in a 2ml collection tube and was centrifuged for 30 seconds at 8000 rpm. The column was then discarded, and 600 ul of 70% ethanol was added to the flow-through (the cellular debris and proteins that pass through the matrix) and thoroughly mixed. Next, 700 ul of the sample was transferred to an RNeasy spin column and centrifuged at 8000 rpm; this time, the resulting flow-through was discarded. 700 ul of Buffer RW1 was then added (in a 2 ml tube) to the same spin column and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 seconds. 500 ul Buffer RPE was added to the spin column and centrifuged under the same conditions (any resulting flow-through was again discarded). This was repeated once more. The RNeasy spin column was transferred to a new 1.5 ml collection tube, and 50 ul of RNeasy free water was added directly to the spin column membrane. It was then centrifuged for one minute at 8000 rpm to elute (release from the matrix) the RNA. Eluting the RNA allowed for its collection and storage to later make complementary DNA (cDNA).

cDNA

To make cDNA, RNA concentrations were determined using a nanodrop machine from MRF. Then, the amount of RNA needed for 1ug RNA concentration per 20ul of cDNA was calculated. To dilute the RNA, the calculated quantity of RNase-free H2O was pipetted into each tube. Next, 5x Buffer and the enzyme Reverse Transcriptase (RT) were added to the tube and mixed well. Lastly, the calculated RNA quantities were pipetted into their respective tubes. The samples were then vortexed in a centrifuge and run in the PCR machine for 40 minutes. The resulting cDNA was then used to perform a quantitative PCR (qPCR).

qPCR

A qPCR was performed to determine the efficacy of each treatment (DMSO, MGD, MK-0752) in downregulating selected downstream target genes of the NOTCH and Wnt β-Catenin pathways. To begin, cDNA was diluted to ¼ (10ul of cDNA to every 30ul of H2O), so the total concentration per sample was 12.5 ng/ul. Next, a mastermix containing Qiagen SYBR, Forward and Reverse primers, and H2O was made. To determine the proper quantities of each component, a pre-set number (10ul for SYBR, 0.4ul for forward and reverse primers, and 7.2ul for H2O) was multiplied by the number of wells in the qPCR plate, plus four extra to increase the margin of error (ex; for a plate with 36 wells, each pre-set quantity would be multiplied by 40). cDNA was then thawed on ice and vortexed in the centrifuge for 30 seconds. 18ul of the reagent mastermix was then pipetted into each well of an empty qPCR plate. The mastermix was followed by 2ul of diluted cDNA per well. Next, the entire plate was securely sealed and spun in the centrifuge. The plate was then transferred to the qPCR machine, which ran for 2 hours. Samples were then removed from the machine and discarded. The machine produced a graph that plotted the number of PCR cycles vs. fluorescent signals (which correlates to the quantity of target RNA in each sample), which was used for subsequent calculations. These calculations allowed researchers to determine the fold change in gene expression for each treatment group/gene combination, thus quantifying treatment efficacy.

Western Blot

A Western Blot was performed to verify the presence of C-myc protein and its expression level, thus allowing researchers to confirm Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity and subsequent treatment efficacy. First, C-myc protein (which had been previously treated with DMSO control or MK-0752) was obtained from a protein concentration assay, and an SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis was conducted. In preparation, 4X Laemmli buffer and lysate were added to 1.5ml microcentrifuge tubes in a 1:4 ratio (regardless of ratios, the volume must never exceed 50ul). Next, a precast gel was removed from its packaging and placed into the gel housing unit of an electrophoresis machine. Its central chamber was then filled with 1X running buffer until the gel was fully submerged. The gel’s comb was removed and each well was filled with 7ul of the aforementioned mixture (the first well was filled with 7ul of ladder). The remaining running buffer was then poured onto the center of the gel. The machine was closed and ran at 150-200V for one hour. While the electrophoresis ran, a nitrocellulose membrane was cut to approximately the size of the gel. The membrane, as well as sponges and filter paper, were then soaked in transfer buffer. The gel was removed from the electrophoresis machine and placed onto the filter paper. The gel/filter paper were transferred to a gel cassette on top of a sponge. An additional sponge was stacked atop the gel/filter paper, and the cassette’s lid was replaced. The cassette was then placed into the plate electrodes and transferred to the buffer tank. The tank was filled to the top with transfer buffer and placed into a cooler with ice. It then ran at 40V for two hours.

Next, the protein detection procedure was performed. To confirm the transfer of proteins, a Ponceau staining was conducted (the membrane was immersed for 5 minutes on a shaker and then washed with TBS-T 5x for 5 minutes). Once protein was identified, the membrane was blocked for 60 minutes in 5% non-milk TBS-T. Next, it was placed into a 50ml conical tube and covered again with 5ml of TBS-T and an appropriate dilution of the primary antibody. The membrane was then incubated overnight at 4℃ on a shaker. The next morning, it was washed three times with TBS-T (each wash was five minutes long). It was then blotted for two hours with the secondary antibody in 5% milk with TBS-T and washed three additional times.

Lastly, a chemiluminescence image (pictured below) was acquired. First, chemiluminescence reagents were mixed (2 ml total in a 1:1 ratio) and poured over the membrane. It was then incubated for five minutes; excess reagent was removed with Kim wipes at the edge of the blot. Lastly, the membrane was placed between two plastic sheets, and present proteins/their expression levels were assessed using ChemiDoc software.

Results:

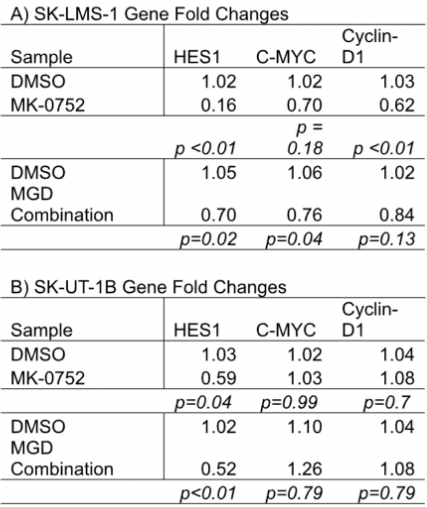

Table 1: qPCR analysis of gene expression

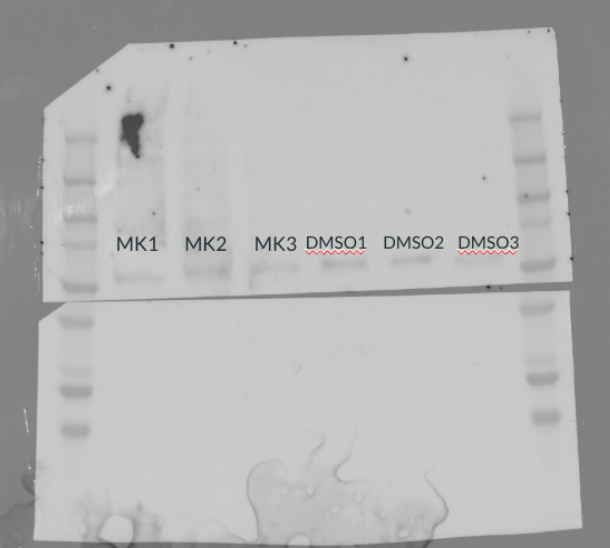

Figure 1: Western Blot analysis of C-myc expression/intensity

Figure 2: Western Blot analysis of GAPDH control expression/intensity

Table 2: Average Intensity and Saturation of C-Myc and Control Proteins in Western Blot

qPCR Results

A qPCR analysis was performed on samples from SK-UT-1B and SK-LMS-1 cell lines treated with DMSO control, MK-0752, or the combination therapy MGD. The fold changes of three downstream target genes (HES1, C-Myc, and Cyclin D1) were measured, and statistical significance was calculated using a Mann-Whitney U test with an alpha level of p <0.01. A fold change of 1 indicates no change in gene expression between experimental and control conditions, while a value <1 indicates a downregulation, and one >1 indicates an upregulation. In the SK-LMS-1 cell line, HES1 had a fold change of 0.16 when treated with MK-0752, 0.70 when treated with MGD, and 1.02 when treated with DMSO. While both MK-0752 and MGD treatments downregulated gene expression, only MK-0752 produced a statistically significant change, with a p-value <0.01. In the same cell line, MGD and MK-0752 treatments downregulated C-Myc expression (fold changes of 0.76 and 0.70, respectively), though not to a statistically significant degree (p-values of 0.04 and 0.18). However, MK-0752 treatment significantly downregulated Cyclin-D1 (fold change of 0.62 and p-value <0.01), indicating some effect on the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway. MGD treatment again downregulated Cyclin-D1 (fold change of 0.84), but not significantly (p-value of 0.13).

In the SK-UT-1B cell line, MGD treatment yielded significant HES1 downregulation (fold change of 0.52 and p-value <0.01). MK-0752, on the other hand, induced a slight but ultimately insignificant downregulation (fold change of 0.56 and a p-value of 0.04). Unlike in the SK-LMS-1 cell line, MGD and MK-0752 treatments slightly upregulated C-Myc and Cyclin-D1 expression. MGD produced a fold change of 1.26 in C-Myc and 1.08 in Cyclin-D1, while MK-0752 produced a change of 1.03 in C-Myc and 1.08 in Cyclin-D1. Thus, both MGD and MK-0752 treatments had a more pronounced effect on the downstream effectors of the NOTCH pathway than on those of the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway.

Western Blot Results

A Western blot was performed to assess C-Myc expression in protein samples. Expression levels were determined by a Western blot imaging machine, which produced values of protein intensity (signal brightness from a protein band) and saturation percentage (the degree to which pixels have reached their maximum possible intensity). Lower protein intensity and saturation percentage indicate low protein expression. MK-0752 treated samples had lower protein intensity and saturation than their DMSO-treated counterparts. MK-0752-treated C-Myc samples exhibited an intensity that was 152.4 steps lower than that of DMSO-treated samples. Saturation was also reduced by 0.44%. This trend was observed in the GAPDH samples ( a control “housekeeping” gene), which showed an average intensity decrease of 395.111 and a 0.89% reduction in saturation.

The western blot also functioned to confirm the identity of present proteins. It is known that C-Myc’s molecular weight is 62 kilodaltons (kD). In Figure 1, the protein ladder aligns at the point corresponding to a weight of roughly 60 kD, identifying the protein as C-Myc.

Discussion:

qPCR

It was hypothesized that MK-0752 would downregulate gene expression in both SK-LMS-1 and SK-UT-1B cell line samples. Further, it was hypothesized that the combination therapy MGD would induce greater downregulation than MK-0752 alone. The results supported the former hypothesis, though not the latter one. The gamma-secretase inhibitor MK-0752 significantly downregulated HES1 in the SK-LMS-1 cell line; this was expected, as HES1 is a downstream target of the NOTCH pathway, which relies on gamma-secretase to function properly. MGD, however, did not significantly downregulate HES1, suggesting that the combination therapy may lack anticipated synergy. This data point is slightly at odds with previous findings, though it is worth noting that past experiments tested MK-0752 in combination with gemcitabine or docetaxel independently of one another (Abedin et al., 2024). It is possible that antagonistic interactions between MK-0752-exposed gemcitabine and docetaxel are to blame for the lack of synergism. The same pattern was reflected in SK-LMS-1 Cyclin-D1 samples, further suggesting that the combination therapy lacks synergism, regardless of the pathway under observation (Cyclin-D1 being a downstream effector of the Wnt B-catenin pathway). A similar pattern was observed in SK-LMS-1 C-myc samples, though MK-0752 did not downregulate gene expression to a significant degree. Nonetheless, it produced a more substantial decrease than did MGD. Across all genes, the gene expression of samples treated with a DMSO control remained unchanged (as was expected).

MK-0752 downregulated HES1 in the SK-UT-1B cell line, though not significantly. This is reflected in previous papers, which found no significant decrease in SK-UT-1B NOTCH signaling when treated with MK-0752 (Abedin et al., 2022). MGD, however, produced a significant downregulation. This is the sole instance of MGD synergism, as the combination therapy produced a more significant downregulation than MK-0752 alone. C-myc and Cyclin-D1, however, responded differently to the treatments. MK-0752 slightly upregulated both C-myc and Cyclin-D1 in the SK-UT-1B cell line. MGD induced a severe upregulation in C-myc and a slighter one in Cyclin-D1. Such findings are consistent with previous studies, which demonstrated that SK-UT-1B cells exhibit lower sensitivity to gamma-secretase inhibitors than SK-LMS-1 cells; this difference in sensitivity may lead to varied gene expression responses (Abedin et al., 2024). Both upregulated genes (Cyclin D1 and C-myc) were downstream effectors of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. A 2013 study found that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is often increased by NOTCH deficiency, as cells may activate alternative pathways to compensate for NOTCH inhibition (Anderson et al., 2013). This resistance mechanism may be responsible for Cyclin D1 and C-myc upregulation in the SK-UT-1B cell line. Like in the SK-LMS-1 cell line, gene expression remained stable in samples treated with a DMSO control.

Ultimately, across both cell lines, MK-0752 was largely more effective than the combination therapy MGD, suggesting that the therapy lacks previously anticipated synergism. Further, gamma-secretase inhibitors were more effective in downregulating downstream effectors of the NOTCH pathway than of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Western Blot

It was hypothesized that C-myc samples treated with the gamma-secretase inhibitor MK-0752 would exhibit lower average intensity and saturation than those treated with the DMSO control. This is visibly reflected in Figure 2, where the MK-0752 treated bands are lighter than those treated with DMSO. Western blot analysis also verified this trend, as the numbers recorded for saturation and intensity post-MK-0752 treatment were lower than those of the control. Such findings support those of previous studies, which found that gamma-secretase inhibitors impair the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thus resulting in the downregulation of its downstream effectors (Barat et al., 2017). Further, the protein ladder aligned at the point corresponding to 62 kD (C-Myc’s molecular weight), confirming the protein’s identity as C-Myc and thus further corroborating the above analysis.

Further research is necessary to corroborate and expand upon this study’s results. To gather more data points (and hopefully yield more significant results), we plan to retreat all cell lines and perform another round of RNA extraction/qPCR. We also plan to use patient samples to perform immunohistochemistry; this will allow for a more thorough assessment of NOTCH and Wnt/B-catenin behavior and the efficacy of gamma-secretase inhibitors in treating uLMS. Mice models will also be used to assess the effect of MK-0752 on tumor growth. Future studies should further examine MGD and similar gamma-secretase/chemotherapy combinations to yield clearer and more definitive insights into their synergistic or antagonistic interactions. Lastly, future research should examine the effects of gamma-secretase inhibitors on the uLMS pathway PI3K/AKT/mTOR (PAM) as well as the NOTCH and Wnt/B-Catenin pathways to provide a more comprehensive understanding of their mechanisms.

Acknowledgments:

Thank you to Dr. Douglas for the opportunity to work in her lab; thank you to Dr. Fife, Tracy Wu, Erik Zhou, Trystyn Murphy, and Kaitlyn Heyt for their contributions to this project. Lastly, thank you to Dr. Koppa for providing edits and insight during the writing process.

Bibliography

Abedin, Y., Gabrilovich, S., Alpert, E., (2022). Gamma secretase inhibitors as potential therapeutic targets for Notch signaling in uterine leiomyosarcoma. National Center for Biotechnology Information, PMC, 23(11), 5980. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9180633/

Abedin, Y., Fife, A., Samuels, C-A., (2024). Combined treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma with gamma-secretase inhibitor MK-0752 and chemotherapeutic agents decreases cellular invasion and increases apoptosis. Cancers (Basel), 16(12), Article 2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122184

Andersen, P., Uosaki, H., Shenje, L., (2013). Non-canonical Notch signaling: Emerging role and mechanism. PMC Home, 22(5), 257–265. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3348455/

Barat, S., Chen, X., Cuong Bui, K., (2017). Gamma-secretase inhibitor IX (GSI) impairs concomitant activation of Notch and Wnt-beta-catenin pathways in CD44+ gastric cancer stem cells. PMC Home, 6(3), 819–829. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5442767/

Sabeh, M, Kumar Saha, S., Afrin, S., (2021). Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in uterine leiomyoma: Role in tumor biology and targeting opportunities. PMC Home, 476(9), 3513–3536. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9235413/

Leave a comment