By: Holly Daykin

Abstract

We conducted an experiment to examine the effect of glycine on depressive-like behavior in mice. We bred mice to have the Nsun2 gene knocked out in their neurons, which removes glycine from the mice’s neurons. Then, three behavioral tests were conducted to compare the depressive-like behavior of the knockout mice and wild-type mice. The results from the behavioral tests showed that the knockout mice exhibited less depressive-like behavior compared to the wild-type mice. So, mice without glycine present in their neurons produce an antidepressant-like phenotype. Our research could potentially promote the use of GLDC and glycine as biological indicators of depression and hopefully lead us to a more effective treatment for this disease.

Introduction

Depressive disorder (depression) is a mental disorder that involves a persistent feeling of sadness and can interfere with day-to-day life. It is increasingly common, particularly among women. It is estimated that 3.8% of the world experiences depression and it is about 50% more common in women than men. Over 700,000 people die from suicide each year, making it the fourth leading cause of death among teenagers and young adults (Depressive Disorder, 2023). Treatments for depression are usually based on the severity of the disease, with psychological treatment and antidepressants being the most effective. Although these are options for battling depression, much ambiguity around the mental disorder remains, and this negatively impacts the lives of about 17 million adults and 3.2 million teenagers in the US (Depression: The Latest, 2023). To combat this disorder more effectively, scientists work to find the root causes of depression.

Recent research has delved into the role of genetics as a potential cause of depression. Family and twin studies have highlighted the large risk of the contribution of genetics to the onset of depressive disorders. However, only a small number of specific genes have been shown to be related to depressive disorders. Epigenetic changes that influence the likelihood of developing depression are of particular interest. Because we often need brain tissue (only possible postmortem) to confirm hypotheses about depressive disorder, animal models of depression are more effective for these studies. Studies have been conducted to identify the most important genes that are related to this disorder. However, conflicting results have failed to explain the specific loci of the risk factors responsible for DDs (Bondarenko & Slominsky, 2018).

Mouse models have been used extensively in research regarding depression and anxiety. The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) knockout mouse, which is derived through cre-recombinase technology, is one of the most accurate models of depression (Krishnan & Nestler, 2011). Glucocorticoids are stress hormones released from the adrenal glands. Although glucocorticoid release occurs periodically, physiological and psychological stressors also stimulate glucocorticoid release. Actions of glucocorticoids are mediated by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (Whirledge & DeFranco, 2018). By generating knockout mice that under or overexpress the GR (while maintaining the regulatory genetic context that controls the GR), we can mimic the human situation of altered GR expression, which is related to hormone-induced stress responses and in turn, depression (Ridder et al., 2005).

Depressive-like behavior can easily be evaluated in mice through conducting behavioral tests. These three tests — forced swim test (FST), tail suspension test (TST), and y-maze test — have been consistently effective at measuring depressive-like behavior. One hypothesis about depressive disorders has to do with the Nsun2 gene and the Glycine decarboxylase (GLDC) protein. Glycine decarboxylase (GLDC) is a protein coded by the Nsun2 gene that breaks down glycine (GLDC Gene, 2020). We focused on Nsun2, because it shapes complex behaviors and neuronal function, directly related to depressive disorder (Blaze et al., 2021). By knocking out the Nsun2 gene, there would be limited GLDC which would lead to an increase in glycine levels (Blaze et al., 2021). Although there is some disagreement on this, one hypothesis is that the increase in glycine should lead to less depressive-like behavior, which is explored through behavioral tests (DeLoye, 2023).

Methods

To conduct this lab, there were three main steps: breeding the mice, behavioral testing, and genotyping. Before we could analyze the depressive-like behavior of the mice, we needed to breed mice with genes that were in line with our hypothesis. The two types of mice we used were knockout (KO) mice and wild-type (WT) mice. The KO mice were bred—using Cre-loxP system technology—to have the GLDC synthesizing part of the NSUN2 gene cut out of the neurons. When the mice are bred, a Cre mouse (has cre-recombinase) is crossed with a LoxP mouse (has LoxP sites). The cre-recombinase is produced and binds to specific LoxP sites on the NSUN2 gene and fluxes out a portion of the NSUN2 gene resulting in the knockout mouse (Kim et al., 2018). The wild-type mice don’t have cre so the deletion cannot occur, meaning GLDC is still present in the neurons.

Once the mice are bred we can conduct the three behavioral tests. There are two standard behavioral tests used to measure behavioral despair in mice, the forced swim test (FST) and the tail suspension test (TST). For both the FST and TST, the mice were either placed in a bucket of water or hung by their tail for 5 minutes and their time spent immobile was recorded. The forced swim test assesses despair based on how the mouse reacts to an unpleasant environment. When placed in water, the mouse will typically try and escape. If it exhibits depressive-like behavior it will float without attempting to escape. The tail suspension test measures the mouse’s response to a stressful situation. The mouse is suspended by its tail and time of immobility is observed. More depressive-like behavior will be exhibited through an increase in time immobile (Wang et al., 2017).

Along with these two behavioral tests we conducted a Y-maze test to highlight cognitive deficits in mice and test their working memory. As the mouse roams throughout the maze, it should show a tendency to explore the less recently visited of the three arms. The percentage of alternation is calculated using the number of arm entries and the number of triads throughout the mouse’s path. Although the Y-maze test doesn’t directly relate to behavioral despair, we conducted the experiment in order to identify a correlation between depressive-like behavior and short-term memory (Y Maze, n.d.).

Finally, once the data from the behavioral tests was collected and recorded (recorded twice and the results were averaged), we conducted gel electrophoresis to genotype each of the mice to re-confirm whether they were KO or WT (homozygous) and to exclude those that were heterozygous. When only top bands are present, it is homozygous for the KO allele. When only the bottom bands are present, it is homozygous for the WT allele, and when both the top and bottom are present, it is heterozygous because it has inherited one of each allele. See image 1 for an example of gel electrophoresis results.

Results

The three graphs in this section are comparisons of means based on the data collected from the three different behavioral tests. We combined the results from both the male and female mice because there wasn’t a notable difference between the results of the two sexes.

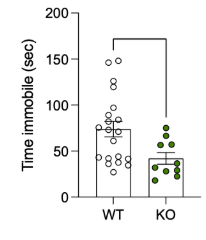

Figure 1 shows the mean amount of time spent immobile by the mice during the forced swim test. The graph shows the difference between the mean time that wild-type mice spent immobile compared to the knock-out mice. The graph demonstrates that the wild-type mice, on average, spent about 25 more seconds immobile than the knock-out mice. The means are significantly different (p < 0.005). Figure 2 indicates the mean amount of time spent immobile by wild-type versus knock-out mice during the tail suspension test. Wild types spent, on average, about 30 more seconds immobile than knock-out mice, with significantly different means (p < 0.02). On the other hand, Figure 3 depicts no significant difference between the wild-type and knockout mice in the Y-maze test (p > 0.9). The graph shows very similar percent alternation averages between the two types of mice.

Figure 1 shows the mean amount of time spent immobile by the WT versus KO mice during the forced swim test. There is a significant difference (p < 0.005).

Figure 2 indicates the mean amount of time spent immobile by wild-type versus knock-out mice during the tail suspension test. There is a significant difference (p < 0.02).

Figure 3 depicts that there is no significant difference between the wild-type and knockout mice in the Y-maze test (p > 0.9).

Overall, Figures 1 and 2 show that wild-type mice spend significantly more time immobile than knock-out mice. This means that WT mice act with more depressive-like behavior than KO mice. Figure 3 demonstrates that working memory doesn’t play a major role in the study.

Discussion

The results from the three behavioral tests are demonstrated in the figures above. As stated above, results indicate that there is a significant difference in time spent immobile between WT and KO mice in both the forced swim and tail suspension behavioral tests. There was, however, no significant difference between their working memory, which was tested in the y-maze test. The significant results from the FST and TST consistently show that WT mice spend more time immobile than KO mice. In this experiment, we use time immobile to represent depressive-like behavior, with more time immobile meaning more depressive-like behavior. Although the y-maze test is one of the three main types of behavioral tests used to observe depressive-like behavior, it focuses on working memory which doesn’t seem to be affected by glycine concentration (as shown by the non-significant results from Figure 3).

Overall, the results show that on average WT mice exhibit more depressive-like behavior than KO mice. While the KO mice were bred to have the GLDC synthesizing part of the NSUN2 gene cut out of the neurons (therefore having a higher amount of GLDC present), GLDC production is still taking place in the WT mice. These results are in line with our hypothesis that more glycine (present in KO mice) leads to less depressive-like phenotypes.

Data from the behavioral tests were recorded twice and the results were averaged together. The standard deviation bars on each figure are relatively small showing that the results are fairly precise. Despite the data being recorded by two different people in two different settings, there is still a possibility of human error. In the future, using a computer to calculate the mice’s time immobile would limit the possibility of human error. There are no obvious errors in the genotyping phase, but human error is always a possibility. In the future, the genotyping process should be conducted more than once as the final step in the lab to gain a stronger level of confidence regarding the genotypes of the mice. Despite the human error inherent in the lab, the results are relatively precise and thus not indicative of major error.

Our experiment helps highlight the role glycine plays in depression. Perhaps further research will be conducted with the hope of being able to use the relationship between glycine and depressive-like behavior to limit depression in humans. All aspects of the relationship between glycine levels and behavior must be observed in mice to see if there are negative effects of knocking out the Nsun2 gene in neurons. Our research could potentially promote the use of GLDC and glycine as biological indicators of depression and hopefully lead us to a more effective treatment for this disease.

Literature Cited

Blaze, J., Navickas, A., Phillips, H. L., Heissel, S., Plaza-Jennings, A., Miglani, S., Asgharian, H., Foo, M., Katanski, C. D., Watkins, C. P., Pennington, Z. T., Javidfar, B., Espeso-Gil, S., Rostandy, B., Alwaseem, H., Hahn, C. G., Molina, H., Cai, D. J., Pan, T., Yao, W. D., … Akbarian, S. (2021). Neuronal Nsun2 deficiency produces tRNA epitranscriptomic alterations and proteomic shifts impacting synaptic signaling and behavior. Nature communications, 12(1), 4913. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24969-x

Blaze, J., Navickas, A., Phillips, H. L., Heissel, S., Plaza-Jennings, A., Miglani, S., Asgharian, H., Foo, M., Katanski, C. D., Watkins, C. P., Pennington, Z. T., Javidfar, B., Espeso-Gil, S., Rostandy, B., Alwaseem, H., Hahn, C. G., Molina, H., Cai, D. J., Pan, T., . . . Akbarian, S. (2021). Neuronal nsun2 deficiency produces tRNA epitranscriptomic alterations and proteomic shifts impacting synaptic signaling and behavior. Nature Communications, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24969-x

Bondarenko, E. A., & Slominsky, P. A. (2018, September 23). Genetics Factors in Major Depression Disease (M. Shadrina, Ed.). Front. Psychiatry. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00334/full

DeLoye, S. (2023, March 31). Newly discovered trigger for major depression opens possibilities for better treatments. Retrieved January 10, 2024, from https://news.ufl.edu/2023/03/glycine-depression/#:~:text=A%20common%20amino%20acid%2C%20glycine,Biomedical%20Innovation%20%26%20Technology%20have%20found.

Depression: The Latest Research. (2023, September 13). WebMD. Retrieved January 9, 2024, from https://www.webmd.com/depression/depression-latest-research

Depressive disorder (depression). (2023, March 31). World Health Organization. Retrieved January 9, 2024, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

GLDC gene. (2020, May 1). MedlinePlus. Retrieved January 10, 2024, from https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/gldc/#:~:text=The%20GLDC%20gene%20provides%20instructions,energy%2Dproducing%20centers%20called%20mitochondria.

Kim, H., Kim, M., Im, S. K., & Fang, S. (2018). Mouse Cre-LoxP system: general principles to determine tissue-specific roles of target genes. Laboratory animal research, 34(4), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.5625/lar.2018.34.4.147

Krishnan, V., & Nestler, E. J. (2011). Animal models of depression: molecular perspectives. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences, 7, 121–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2010_108

Ridder, S., Chourbaji, S., Hellweg, R., Urani, A., Zacher, C., Schmid, W., Zink, M., Hörtnagl, H., Flor, H., Henn, F. A., Schütz, G., & Gass, P. (2005). Mice with genetically altered glucocorticoid receptor expression show altered sensitivity for stress-induced depressive reactions. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 25(26), 6243–6250. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0736-05.2005

Wang, Q., Timberlake, M. A., Prall, K., & Dwivedi, Y. (2017). The recent progress in animal models of depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 77, 99-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.04.008

Whirledge, S., & DeFranco, D. B. (n.d.). Glucocorticoid Signaling in Health and Disease: Insights From Tissue-Specific GR Knockout Mice. National Library of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2017-00728

Y Maze Spontaneous Alternation Test. (n.d.). Stanford Medicine. Retrieved January 10, 2024, from https://med.stanford.edu/sbfnl/services/bm/lm/y-maze.html#:~:text=Testing%20occurs%20in%20a%20Y,a%20less%20recently%20visited%20arm.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jen Blaze and Schahram Akbarian for allowing me to work in their lab this summer and serving as mentors for me. Thank you to Mr. Waldman for his support and guidance throughout the writing process.

Leave a comment