By Sophia Thompson

Abstract:

Radiopharmaceuticals represent a cutting-edge cancer diagnosis and treatment approach by combining radioactive isotopes with active molecules for targeted delivery. This study examines the potential of active targeting with the humanized monoclonal antibody sibrotuzumab, which binds to the fibroblast activation protein FAP, a protein overexpressed by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in the tumor microenvironment. Utilizing U-87, glioblastoma cells that endogenously express FAP, the binding affinity, and internalization of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-sibrotuzumab were examined through antibody internalization assay at 4 and 37 degrees Celsius. Before the execution of the assay, successful bioconjugation of the antibody with the chelator DFO was confirmed by conducting an iTLC analysis and radiolabeling with zirconium-89. The results of this assay demonstrated consistent membrane binding of over 50% at both temperatures. This indicates a strong affinity for sibrotuzumab for FAP. The internalization rates for FAP varied with temperature and were relatively; however, because the primary aim of this study was to validate FAP as a viable target for future radiopharmaceutical development, and the internalization rates do not affect its viability as a target, it is just an extra statistic. These findings support further investigation into sibrotuzumab-FAP targeting in more complex tumor models. This can include in vivo biodistribution studies and tumor microenvironment simulations.

Introduction:

Radiopharmaceuticals are vital to the healthcare industry. They serve as an intersection between medicine, chemistry, and radioactivity, a new field that is evolving every day.1 Nuclear medicine procedures are instrumental in imaging and targeting malignancies; millions are performed yearly. Designing and engineering radiopharmaceuticals is a complicated process that requires multiple factors to align for the drug to work. Choosing the appropriate nuclide is critical as each has a specific half-life and decay type that must be worked with and around to create a successful radiopharmaceutical. These factors impact the utility and localization of radiopharmaceutical products as well. Molecular stability, ease, and production cost are also critical when designing radiopharmaceuticals, as the field is costly and often challenging to produce results quickly. 2

The combination of radioisotopes and medicine is an integral part of modern medicine. It combines innovation and science to transform disease diagnosis, treatment, and understanding. Radioisotopes act as invisible markers, allowing medicines to go beyond what most understand as traditional medicine. They are much more customizable to each patient, assisting in making treatments more effective and lowering side effects.

In the quest for the best radiopharmaceutical cancer treatments, scientists explore the best combinations of the pieces explained below. There are two main types of radiopharmaceuticals: passive targeting and active targeting. This paper will focus on active targeting, which this project focuses on as its research into radiopharmaceutical anticancer treatments. Active targeting is an approach in which a ligand, usually an antibody, small molecule, or peptide, is attached to a radioactive molecule, a radioisotope. This targeting method is specifically designed to deliver radiation to cancer cells or the stroma of cancer cells that express specific receptors.

1 Shivang Dhoundiyal et al., “Radiopharmaceuticals: Navigating the Frontier of Precision Medicine and Therapeutic Innovation,” European journal of medical research, January 5, 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10768149/.

2 Akul Munjal, “Radiopharmaceuticals,” StatPearls [Internet]., June 20, 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554440/.

This method minimizes the toxicity of radiopharmaceuticals and enhances their therapeutic effectiveness. 3 There have been several successful radiopharmaceuticals that use active targeting, including Lutetium-177 (Lutathera), which was approved by the FDA in 2018, targeting the somatostatin receptor overexpressed in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. 4 Another example is Technetium-99m, mainly used in diagnostic imaging. 5

Compared to older treatment methods, modern radiopharmaceuticals specifically deliver radiation therapy. Unlike external radiation, which can often cause collateral damage, as normal tissue has to be hit to get to cancer, radiopharmaceuticals can provide radiation therapy directly and specifically only to cancer cells, potentially reducing the short and long-term side effects of radiation treatment.6

Radiopharmaceuticals are drugs that consist of a radioactive form of chemical elements known as radioisotopes.7 Radiopharmaceuticals can be given orally, by injection, or intravenously, and their distribution can be monitored by screening with PET/CT, SPECT, or Gamma cameras. Radiopharmaceuticals must target a specific body area because of their highly toxic nature. Radiopharmaceuticals consist of four pieces: the radioactive isotope of a metal, a chelator, a linker, and a targeting molecule. While the purpose of a drug can determine the choice of radiometal, our lab was interested in exploring a specific antibody. So therefore, the radiometal came last, as it was first looked at to see which chelator works with the antibody and which radiometal can work with that chelator.

Radioligands can emit EC (electron capture), 𝛽 + decay,

𝛽- decay, and ∝ decay. 𝛽 + decay and 𝛽- decay are involved in positron emission tomography. When an annihilation reaction occurs, gamma waves shoot 180 degrees, creating an image that shows where the radiopharmaceutical is in the body.

3 Munjal, “Radiopharmaceuticals.”

4 Munjal, “Radiopharmaceuticals.”

5 Cleveland Clinic medical professional, “Get to Know Radiopharmaceuticals,” Cleveland Clinic, March 19, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/radiopharmaceuticals.

6 2025 February 13, 2025 January 2, and 2024 December 11, “Radiopharmaceuticals Emerging as New Cancer Therapy,” Radiopharmaceuticals Emerging as New Cancer Therapy – NCI, accessed March 31, 2025, https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/radiopharmaceuticals-cancer-radiation-therapy#:~:te xt=Radiopharmaceuticals%20consist%20of%20a%20radioactive,linker%20that%20joins%20the%20two.&text=The

%20past%20two%20decades%20have,grow%2C%20divide%2C%20and%20spread.

7 Andrea Galindo and International Atomic Energy Agency, “What Are Radiopharmaceuticals?,” IAEA, February 26, 2025, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/what-are-radiopharmaceuticals.

A bifunctional chelating agent (BFC) must bind the radiopharmaceutical to the targeting molecule to bind the two together. The BFC attaches to the radioisotope and can also attach to the linker, functioning as both a transitional piece and a protector of the radioisotope. This ensures that the radioisotope is not released into the body while in transit to its targeted location. 8 The BFC protects the radioligand from competing bioligands and attaches it to the drug’s targeting agent. A linker connects the BFC radiometal piece to the targeting molecule. It can be optimized to improve tumor uptake, distribution, and pharmacokinetics. 9

Targeting molecules can vary dramatically depending on the radiopharmaceutical. Generally, targeting molecules are small molecule inhibitors or antibodies pertaining to radiopharmaceuticals. These targeting molecules aim at specific genes, proteins, and other molecules involved with cancer cells’ growth, spread, and survival. The targeting molecule binds to its target, and therefore, the rest of the radiopharmaceutical is attached, and the radioactive compound can decay. 10

8 Andrea Galindo and International Atomic Energy Agency, “What Are Radiopharmaceuticals?,” IAEA, February 26, 2025, https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/what-are-radiopharmaceuticals.

9 “Alpha-9 Oncologys: Radiopharmaceuticals: Cancer Therapy: Approach,” Alpha-9 Oncology, January 11, 2025, https://www.a9oncology.com/our-approach/#:~:text=The%20linker%20connects%20the%20binder,isotope%20com patibility%20and%20radiolabeling%20efficiency.

The Jason Lewis lab focuses on developing radiopharmaceuticals for targeted diagnosis and treatment of cancer. In my project, we looked at the antibody sibrotuzmab, a humanized monoclonal antibody intended for cancer treatment.11 It targets the fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a protein expressed by Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs), a group of activated fibroblasts that secrete a variety of factors regarding tumor regulation. 12 The goal of this project was to look at the internalization and the binding of the antibody sibrotuzmab to FAP and to determine its affinity to FAP as a target; see Appendix 2 for more details.

Methods:

We used bioconjugation and cell culturing to develop the cells necessary to perform the antibody internalization assay. The cell line U-87, a glioblastoma cell line, was used as a model for this experiment, as U-87 endogenously expresses the FAP target. U-87 cell line was grown in media, MEM+NEAA+10% FCS, and was grown in flasks. The steps were as follows.

⦁ We performed a bioconjugation to bind the Sibrotuzumab antibody with DFO in DMSO. This was completed twice, with a new batch of DFO used the second time. The DFO dissolved successfully in DMSO, allowing for the correct ratio of DFO in DMSO, as stated in the procedure (Appendix One).

10 “NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms,” Comprehensive Cancer Information – NCI, accessed March 31, 2025, https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/molecular-target.

11 “Sibrotuzumab,” Sibrotuzumab – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics, accessed March 31, 2025, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/sibrotuzumab.

12 Dakai Yang et al., “Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: From Basic Science to Anticancer Therapy,” Nature News, July 3, 2023, https://www.nature.com/articles/s12276-023-01013-0.

⦁ U87 cells were cultured for five weeks to perform an antibody internalization assay. The cells were grown in flasks containing media. Cells were grown on the flask’s long, flat, horizontal side. The media was changed every 2-4 days based on the media’s color and then the cells’ concentration in the flask. The higher the concentration, the more often the media needed to be changed and the higher the likelihood that the cells needed to be split into more flasks to prevent their death. When splitting cells, trypsin was used to remove the cells from the wall of the flask, and for every unit of trypsin, an equal amount or more of media was used to ensure that the trypsin did not kill the cells. After this cell mixture was created, it was centrifuged to isolate the cells for their transfer into new flasks. See Appendix Two for a more specific procedure.

⦁ Once the cells were grown and the bioconjugation completed, a test radiolabeling was performed to ensure its success. An iTLC test was performed to double-check that the zirconium stuck onto the bioconjugation instead of traveling up the strip. This was successful; therefore, this bioconjugated piece could be used for the antibody internalization assay. Radiolabeling is a very time-sensitive procedure. It was important to consistently mark the time and the number of millicuries in the amount of ml Zr-89 at every step of the procedure.

⦁ As stated in the procedure above, an antibody internalization assay was completed utilizing bioconjugation. 3μl of radioligand was placed in each Eppendorf tube, which held 200μl of U87 cells. Half of the cells were incubated at 37C, and the other half at 4C, to test for the effect of temperature on the internalization assay. This was done for 90 minutes, and the cells were tapped/shaken up and down every 15 minutes. Once incubated, each tube was centrifuged to remove the supernatant, then wash 1, wash 2, glycine 1, glycine 3, and finally hydroxide. These tubes were promptly placed on the gamma counter to determine the amount of radioactivity in each before all radioactivity was gone.

Experimental Results:

This experiment aimed to determine the percentage of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-sibrotuzumab bound to the membrane of the U-87 cell and then the amount that was internalized into the cell. This required testing iTLC to ensure that the iTLC machine was working correctly. Then, an iTLC test was performed on the radiolabeled bioconjugated piece to ensure that it was properly radiolabeled before using [89Zr]Zr-DFO-sibrotuzumab to conduct the antibody internalization assay to see how much of the radioligand was internalized and how much bound to the membrane. Additionally, temperature was considered a variable, with 4 degrees and 37 degrees Celsius being the two different temperatures at which this experiment was conducted.

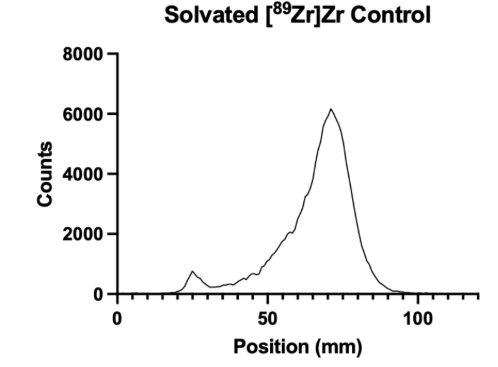

Figure 1: Control iTLC Test

Figure 1 presents a control iTLC test of solvated [89Zr]Zr, demonstrating an incorrect iTLC and what it looks like when the [89Zr]Zr is not correctly radiolabeled to the bioconjugation piece. The initial small spike is where the solution was pipetted onto the 100 mm strip, between approximately 20mm and 30mm up the strip.

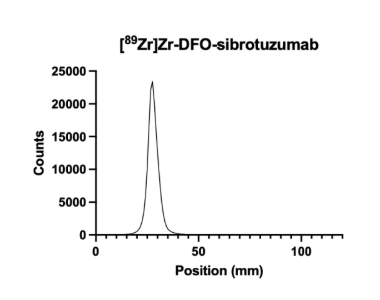

Figure 2: iTLC Test of the Bioconjugation with [89Zr]Zr-DFO-sibrotuzumab

Figure 2 presents a successful radiolabeling of [89Zr]Zr with sibrotuzumab. The radiolabeled solution was placed approximately 25-35mm up the strip. The solution stayed there, and the [89Zr]Zr did not travel up the sheet, indicating that the [89Zr]Zr bonded correctly to the bioconjugated piece.

Table 1: Antibody Internalization Assay at 37 Degrees

Table 1 presents the data of the antibody internalization assay at 37 degrees Celsius. This experiment was repeated three times, and the average of those repetitions is indicated on the bottom of this table.

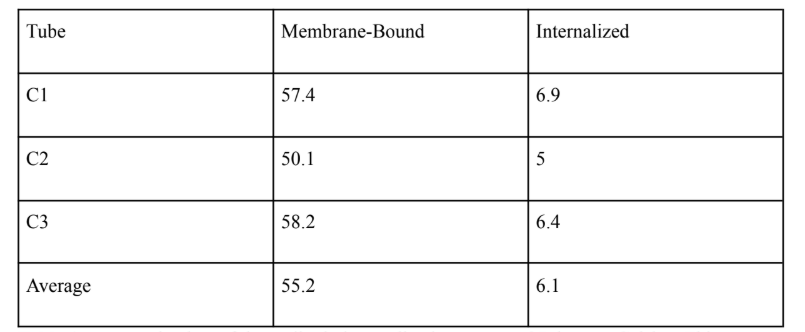

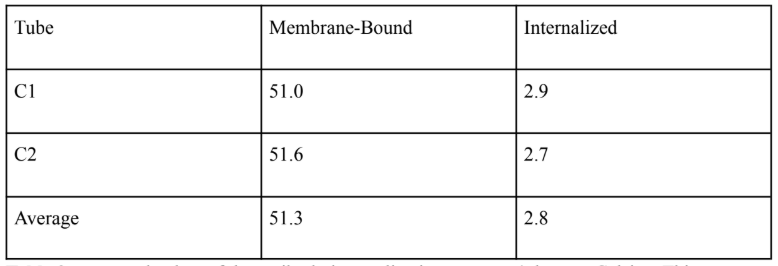

Table 2: Antibody Internalization Assay at 4 Degrees

Table 2 presents the data of the antibody internalization assay at 4 degrees Celsius. This experiment was repeated three times, and the average of those repetitions is indicated at the bottom of this table.

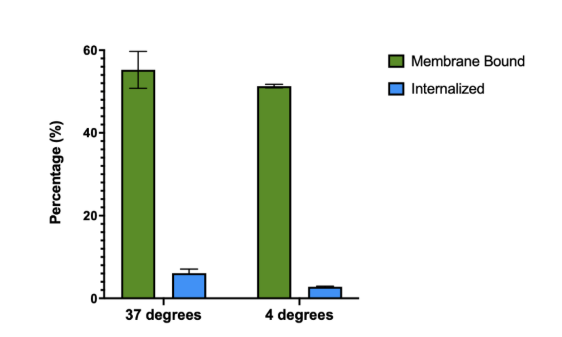

Figure 3: Average Percent of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-sibrotuzumab Membrane-Bound and Internalized at 37 degrees and 4 degrees Celcius

Figure 3 presents the average percentage of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-sibrotuzumab that is membrane-bound and the average percentage of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-sibrotuzumab that is internalized at 37 degrees and 4 degrees.

Discussion:

This project aimed to look at the internalization and the binding of the antibody sibrotuzmab to FAP and to determine its affinity to FAP as a target. The affinity to the FAP was found to be quite high, and the data can be used to continue this experiment and utilize the FAP as a target when creating radiopharmaceuticals. Before this experiment could be conducted, it was essential to ensure that the bioconjugation had been successful. The bioconjugation links the chelator with the antibody sibrotuzmab, the targeter of the FAP. If these molecules are not linked properly, the radioligand (the chelator and radioactive material) could detach from the radiopharmaceutical, potentially harming the organism it is in. Free-floating radioligands can go into the bloodstream and the bones and be potentially lethal. The next step of an experiment like this is a biodistribution study, in which small animals are injected with radiopharmaceuticals and assayed for radiation at different locations throughout the body and in the tumor. An intermediate step is to radiolabel a solvated control and the bioconjugated piece and to test its success with an iTLC test strip. In our experiment, the control was shown in Figure 1, and the successful radiolabeling of DFO-sibrotuzumab with [89Zr]Zr is shown in Figure 2.

We performed the test by radiolabeling a solvated [89Zr]Zr control to demonstrate what a successful bioconjugation should not look like and then performing an actual radiolabeling of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-sibrotuzumab. By comparing the two graphs, Figure 1 and Figure 2, it is clear that the radiolabeling of the control is not successful, as expected. This is clear by the shape of the graph; between 20-30mm up the iTLC strip, there is a small peak where the main peak should be, and there is a large peak further up the iTLC strip, meaning that the radioligand has been carried up, and was not successfully attached to the bioconjugated molecule. Figure 2 shows the graph’s peak at 20-30 mm, meaning that it was successfully bioconjugated because the radioligand was not carried up the strip.

The second part of this experiment could be conducted with a successfully bioconjugated ligand. An antibody internalization assay could be performed to examine the amount of sibrotuzumab that would bind to the outside of the cell and the amount that would be internalized into the cell. The measurement of the amount internalized was not necessary to conclude the results of this experiment, the goal of which was just to test the FAP as a target, which is on the outside of the cell. However, because of the model cell used, U-87, FAP as a target is also in the inside of the cell. The assay broke down each cell layer by doing many different washes, including a media wash, two glycine buffer washes, and two hydroxide buffer washes. Each wash allowed for different breakdowns of the cell so that the gamma counter could look at the amount of the radioligand not attached (the media wash), the amount of radioligand attached to the membrane (the glycine buffer washes), and the amount of radioligand internalized into the cell (the hydroxide washes). Figure 3 shows the average percent internalized and the average percent membrane bound at 37 degrees and 4 degrees. Both temperatures had an average percent membrane-bound above 50%, which is promising. The target, FAP, is considered a type of CAF (cancer-associated fibroblast), which is the most prevalent TME (tumor micro-environment) cell; having numbers above 50% means that sibrotuzumab is a good targeting molecule for attaching onto the FAP, and is the reason why the amount of sibrotuzumab internalized is not important.

A limitation of this test of FAP as a target with sibrotuzumab is that this model does not test FAP as a target in a CAF in a TME. Without testing FAP as a target in the appropriate environment, one cannot know for sure that the sibrotuzumab would successfully bind to the FAP. However, despite this limitation, this study does show that sibrotuzumab has a strong affinity for FAP as a target.

Future experiments could include creating a TME with CAFs to test FAP as a target in its actual environment, as stated above. Another continuation of this study would be to do a

bio-distribution at different time intervals to test how long sibrotuzumab stays bound at its target, the FAP, on the surfaces of the U-87 tumor cells. Our experiments show that sibrotuzumab is at least promising as an anticancer agent, and we hope that future in-vivo experiments will validate this.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1: Bioconjugation Procedure (taken from Dr. Aiden Ingham)

Bioconjugation Materials:

⦁ PBS, pH ~7.2; Amicon spin filters (30 kDa); Eppendorfs; pipets (10, 200 and 1000 μL); Antibody; DFO-NCS, Mw = 752.9 g/mol; DMSO; Na2CO3 solutions (0.1 M and 0.01 M); HEPES (1 M); and size exclusion, PD 10 columns

Procedure:

⦁ Thaw 1-2 mg of antibody (AB) in x μL from -80 ℃ freezer.

⦁ Pipet AB solution into an amicon spin filter (30 kDa, 0.5 mL)

⦁ Rinse AB Eppendorf with 500 – x μL of PBS, pH ~7.2, and transfer to AB-containing spin filter.

⦁ To balance centrifuge, pipet 500 μL PBS solution into another amicon bottom container and place the amicons opposite one another.

⦁ Spin down filter to ~100 μL by setting the cent

⦁ rifuge to 12,000 × g for 5 minutes.

⦁ Empty the bottom of the amicon spin filter set-up (but not the AB solution in the filter).

⦁ Refill the filter back up to 500 μL with PBS, pH ~7.2.

⦁ Centrifuge down to ~100 μL and repeat 1 to 2 more times to thoroughly wash the AB.

⦁ In a lo-binding Eppendorf tube, collect the 100 μL mAb portion.

⦁ Rinse the spin filter with an extra 100 μL of PBS and add to AB solution.

⦁ Note: want final AB conc > 2 mg/mL but want DMSO < 2%. Thus 1 mg AB in a volume

~ 200 – 250 μL is ideal since 3 μL* DFO-NCS in DMSO will be used.

⦁ Confirm concentration is adequate (2-10 mg/mL) using the nanodrop (1.5 to 2 μL per drop for accurate measurement).

⦁ Make sure nanodrop is well cleaned, blank sample runs well and sample runs have no air bubbles. Also use the IgG setting under the ‘proteins’ selection.

⦁ Raise the pH of the AB solution to pH 8.5 – 9.0 using 1 μL HEPES (1M) and a few μL of Na2CO3 (0.1 M and 0.01 M).

⦁ Mix in the DFO, check the final pH, and put on the thermomixer for 1 h at 37 ℃.

⦁ While reaction is going, wash and equilibrate PD 10 column with PBS pH ~7.2 (25 mL).

⦁ Once the conjugation reaction has finished, load the sample onto the equilibrated PD 10 column and let the solution go into the bed. Note: it’s good to load ~ 0.5 mL AB solution on to PD-10 column, so can dilute AB-DFO solution with PBS just before loading onto the column.

⦁ Add 2.0 mL PBS and let it pass through the PD10 column.

⦁ After, add 1 mL of PBS at a time, and collect in separate, labeled Eppendorf tubes.

⦁ Confirm the concentration of AB in Eppendorfs 1-4. (Should be in Eppendorf 1 & 2).

⦁ Concentrate down the appropriate Eppendorf tubes in amicon spin filters and get a total AB-conjugate volume of ~200 μL.

⦁ Make a final note of the concentration using the nanodrop since this is the calculation used for radiolabeling/radiopharmaceutical preparation.

⦁ Store aliquoted AB-DFO conjugate in -80 ℃ freezer – if AB does not function well with this additional freeze-thaw, leave conjugate in 4 ℃ fridge for a few weeks and prepare on smaller scale more frequently.

⦁ Final note: write down all the μL of solutions, even when 2 μL taken out for nanodrop measurements. This will help approximate concentrations better.

*The desired DFO-NCS solution concentration is 10 mg/mL: 1 mg of DFO-NCS in 100 μL of DMSO is a good volume to aliquot and store in -20 ℃.

*Continued: want to add 6-8 molar equivalents of DFO and make sure the DMSO < 2% of the total reaction mixture volume.

An example of the maths: 2 mg mAb / Mw of AB (150,000 g/mol) = 1.33 x 10-8 mol

1.33 x 10-8 mol x 6 equivalents = 8 x 10-8 mol

To get the mass of DFO-NCS: 8 x 10-8 mol x 752.9 g/mol = 6.0 x 10-5 g (or 0.060 mg) Finally, the volume of DFO to add: 0.060 mg / 10 mg/mL = 6 μL

To get < 2%, the total reaction volume should be: 300 μL or more – dilute the AB solution if necessary and check the final concentration is still 2-10 mg/mL on the nanodrop.

*Can divide the above by 2 if 1 mg of AB used, e.g. 3 μL of DFO-NCS in DMSO and minimum conjugation reaction volume of 150 μL.

Appendix 2: Cell Culturing Procedure (Taken from Dr. Aiden Ingham)

Cell culturing Before starting:

⦁ Check cell morphology and culture conditions on ATCC website.

⦁ Order appropriate media, phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and trypsin.

⦁ Using the bead bath, warm up PBS and media between room temperature (RT) to 37 ℃.

⦁ Spray down the biosafety cabinet (BSC) using ethanol 70% solution, then turn the UV lamp on for ~15 min.

⦁ After, turn off the UV lamp and the BSC is ready for use.

⦁ Note: spray down anything before it enters the BSC including your gloves, and keep things packaged/unopened until they’re inside.

⦁ Also: the pipets and aspiration tubes can be attached to pipet gun with just the top of the package open and sliding the package off without touching the pipet directly. This will provide better sterility/contamination control.

Thawing:

⦁ Find location from cell inventory. Then, from the cryogenic storage Dewar on 20th floor, remove cells.

⦁ Thaw cells in bead bath (37 ℃). Thaw for a few minutes or until the solution moves

when the vial is tilted. Note: don’t leave for too long as the cells are in DMSO.

⦁ Add 9 mL of media to falcon tube.

⦁ Pipet 1 mL of cell stock into the falcon tube (vt = 10 mL).

⦁ Centrifuge the falcon tube to form a pellet of cells at 125 × g (relative centrifugal force

(RCF)) for 5 to 7 minutes.

⦁ Note: maximum g-force for cells is 500 – higher force may damage them. Also, make sure centrifuge is balanced using a separate falcon tube with water added to correct level.

⦁ Aspirate the media containing DMSO.

⦁ Resuspend cell pellet with 10 mL media – careful not to splash cells/media out the tube.

⦁ Add 5 mL cell media to T-75 flask, followed by the 10 mL falcon tube solution.

⦁ Slide flask back and forth, and side to side, but not in a circular motion.

⦁ Make sure media, flask and falcon tube are appropriately labeled. Flask should be labeled with name, cell line, date and passage number.

Media change:

Let media warm up to avoid ‘cell shock’. Aspirate old media and replace with new media. PBS wash may not be necessary and uses up plastics.

Expanding or splitting cells:

Let solutions warm up. Aspirate media, wash with PBS (more important to wash to remove media before trypsin), aspirate PBS, and add trypsin. Can wait 5-10 minutes for cells to lift off. Putting the flask into the incubator for a couple of minutes may speed up this process. Then neutralize trypsin with an equal portion of media, transfer to falcon tube, form pellet and aspirate solution. Resuspend the cells and count the number. Be careful with the math and dilution factor.

Cells may take a couple of days to settle on the flask and form their usual adherence morphology.

Bibliography:

“Alpha-9 Oncologys: Radiopharmaceuticals: Cancer Therapy: Approach.” Alpha-9 Oncology, January 11, 2025.

https://www.a9oncology.com/our-approach/#:~:text=The%20linker%20connects%20the% 20binder,isotope%20compatibility%20and%20radiolabeling%20efficiency.

Author links open overlay panelC.-H. Chang, and AbstractBifunctional chelating agents are molecules which can both bind metal ions and be attached to other molecules. They permit the preparation of radiopharmaceuticals by last-minute addition of radioactive metal ions to chelate-tagged molecules such a. “Bifunctional Chelating Agents: Linking RADIOMETALS to Biological Molecules.” Applications of Nuclear and Radiochemistry, November 17, 2013. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780080275444500162#:~:text=Bi functional%20chelating%20agents%20are%20molecules,such%20as%20proteins%20or% 20polypeptides.

Author links open overlay panelMuhammad Tufail, AbstractThe tumor microenvironment (TME) holds a crucial role in the progression of cancer. Epithelial-derived tumors share common traits in shaping the TME. The Warburg effect is a notable phenomenon wherein tumor cells exhibit resistance to apoptosis an, N.M. Anderson, M.V. Berridge, R.J. Boohaker, G. Cassinelli, J. Chen, et al. “Unlocking the Potential of the Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy.” Pathology – Research and Practice, October 4, 2023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0344033823005472.

Dhoundiyal, Shivang, Shriyansh Srivastava, Sachin Kumar, Gaaminepreet Singh, Sumel Ashique, Radheshyam Pal, Neeraj Mishra, and Farzad Taghizadeh-Hesary.“Radiopharmaceuticals: Navigating the Frontier of Precision Medicine and Therapeutic Innovation.” European journal of medical research, January 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10768149/.

Dhoundiyal, Shivang, Shriyansh Srivastava, Sachin Kumar, Gaaminepreet Singh, Sumel Ashique, Radheshyam Pal, Neeraj Mishra, and Farzad Taghizadeh-Hesary. “Radiopharmaceuticals: Navigating the Frontier of Precision Medicine and Therapeutic Innovation.” European journal of medical research, January 5, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10768149/.

February 13, 2025, 2025 January 2, and 2024 December 11. “Radiopharmaceuticals Emerging as New Cancer Therapy.” Radiopharmaceuticals Emerging as New Cancer Therapy – NCI. Accessed March 31, 2025.

https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/radiopharmaceuticals-canc er-radiation-therapy#:~:text=Radiopharmaceuticals%20consist%20of%20a%20radioactive

,linker%20that%20joins%20the%20two.&text=The%20past%20two%20decades%20have, grow%2C%20divide%2C%20and%20spread.

Galindo, Andrea, and International Atomic Energy Agency. “What Are Radiopharmaceuticals?” IAEA, February 26, 2025. https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/what-are-radiopharmaceuticals.

Moravek. “What Is Radiochemistry and Why Do We Need It?” Moravek, Inc., March 21, 2022. https://www.moravek.com/what-is-radiochemistry-and-why-do-we-need-it/.

Munjal, Akul. “Radiopharmaceuticals.” StatPearls [Internet]., June 20, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554440/.

“NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms.” Comprehensive Cancer Information – NCI. Accessed March 31, 2025.

https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/molecular-target.

professional, Cleveland Clinic medical. “Get to Know Radiopharmaceuticals.” Cleveland Clinic, March 19, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/radiopharmaceuticals.

“Radiochemistry.” Radiochemistry – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed March 31, 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/physics-and-astronomy/radiochemistry.

“Sibrotuzumab.” Sibrotuzumab – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Accessed March 31, 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/sibrotuzumab.

Yang, Dakai, Jing Liu, Hui Qian, and Qin Zhuang. “Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: From Basic Science to Anticancer Therapy.” Nature News, July 3, 2023. https://www.nature.com/articles/s12276-023-01013-0.

Leave a comment