By: Meredith Metz, Rose Posternak, and Mia Seshadri

Abstract:

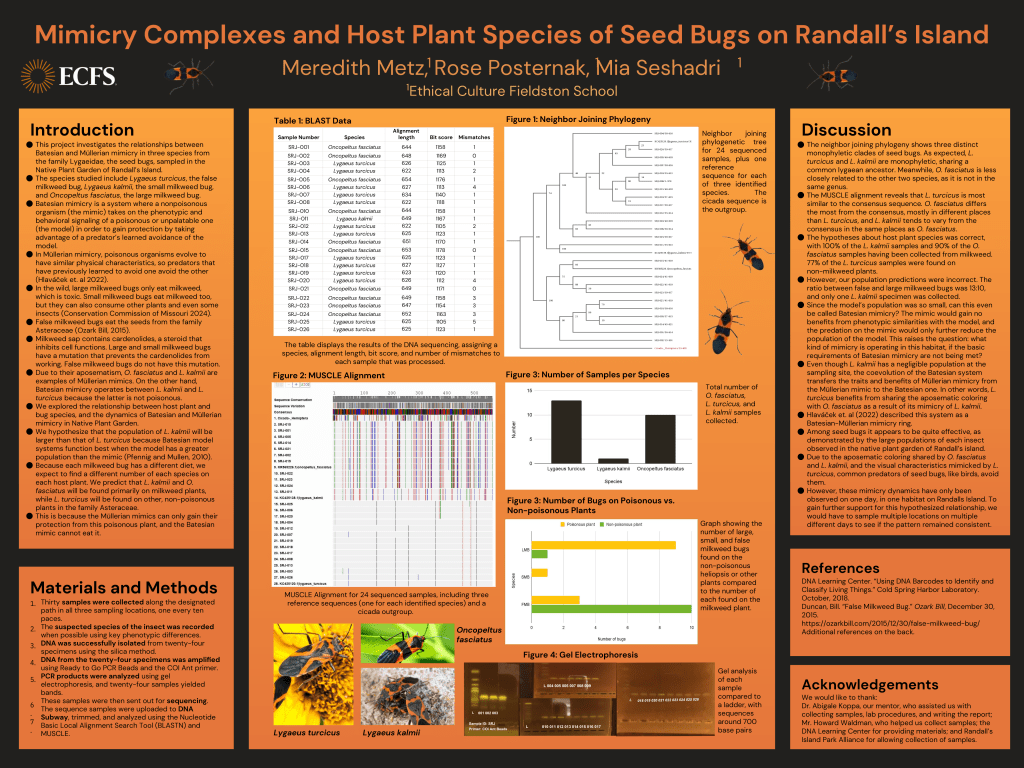

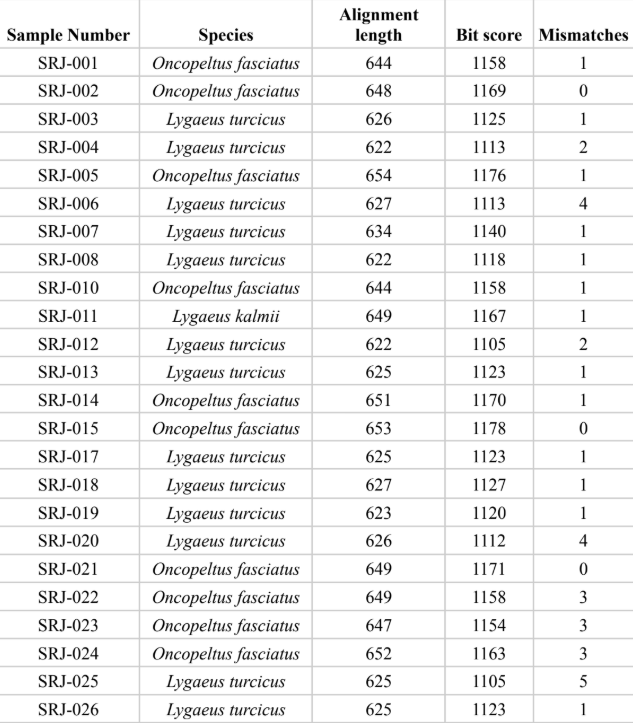

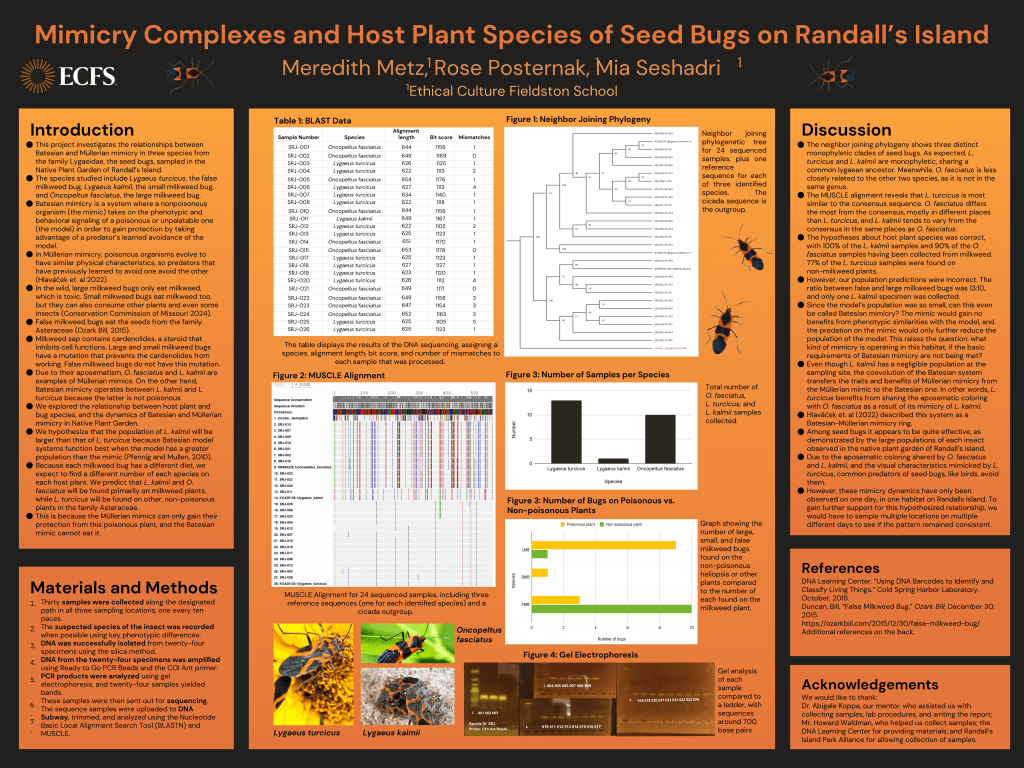

This study discusses mimicry patterns and host plant choice in large (Oncopeltus fasciatus), small (L. kalmii), and false (Lygaeus turcicus) milkweed bugs, all species in the family Lygaeidae. 30 samples were collected from the Native Plant Garden on Randall’s Island, yielding 24 successful DNA sequences. After sequencing, the species identifications of the 24 samples were confirmed: 10 were O. fasciatus, 13 were L. turcicus, and one was L. kalmii. The majority of both large and small milkweed bugs were found on milkweed, while the false milkweed bugs were found mainly on heliopsis, following expected patterns. Observed population ratios suggest a system of mimicry relying on both Batesian and Müllerian mimicry is in place in this habitat, as ratios typical of classic Batesian mimicry were absent.

Introduction:

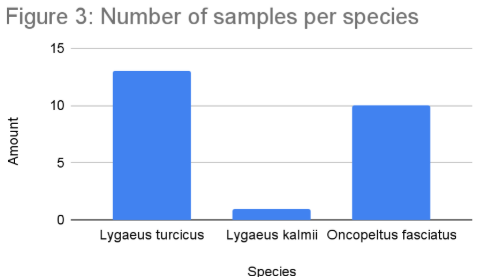

This project investigates the relationships between Batesian and Müllerian mimicry in three species from the family Lygaeidae, the seed bugs. The species studied include Lygaeus turcicus, the false milkweed bug, Lygaeus kalmii, the small milkweed bug, and Oncopeltus fasciatus, the large milkweed bug. They were sampled in the Native Plant Garden of Randall’s Island. Batesian mimicry describes a system where a nonpoisonous organism (the mimic) takes on the phenotypic and behavioral signaling of a poisonous or unpalatable one (the model) in order to gain protection by taking advantage of a predator’s learned avoidance of the model. In Müllerian mimicry, poisonous organisms evolve to have similar physical characteristics, so predators that have previously learned to avoid one avoid the other (Hlaváček et. al 2022).

In the wild, large milkweed bugs only eat milkweed. They use their proboscis to suck the sap out of seeds, leaves, and stems (Conservation Commission of Missouri 2024). Small milkweed bugs eat milkweed too, but they also consume flower nectar and sap from other plants. Additionally, they can eat the larvae, pupae, and adults of some species of Diptera, Hymenoptera, and Coleoptera (Conservation Commission of Missouri 2024). False milkweed bugs eat the seeds from the family Asteraceae (Ozark Bill, 2015). At Randall’s Island, this family includes heliopsis, asters, and goldenrod. Milkweed sap contains cardenolides, a kind of cardiac glycoside. It inhibits the sodium-potassium pump, which is present in all animals. The large and small milkweed bugs have specialized mutations in their Na+/K+ ATP-ase that prevent the cardenolides from binding and inhibiting the pump. They can survive up to 200 nanomoles of cardenolides and are known to sequester this molecule as well, which is what makes them poisonous if eaten (Heyworth 2022). However, false milkweed bugs do not have this mutation. Due to their aposematism, O. fasciatus and L. kalmii are examples of Müllerian mimics. On the other hand, Batesian mimicry operates between L. kalmii and L. turcicus because the latter is not poisonous.

Our project aims to explore the relationship between host plant and bug species, and the effectiveness of Batesian and Müllerian mimicry in the native plant garden of Randall’s Island. We hypothesize that the population of L. kalmii will be larger than that of L. turcicus because Batesian model systems can only function when the ratio of model to mimic is greater than one (Pfennig and Mullen, 2010). Because each milkweed bug has a different diet, we expect to find a different number of each species on each host plant. We predict that L. kalmii and O. fasciatus will be found primarily on milkweed plants, while L. turcicus will be found on other, non-poisonous plants in the family Asteraceae. This is because the Müllerian mimics can only gain their protection from this poisonous plant, and the Batesian mimic cannot eat it.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty samples were collected along the designated path in one every ten paces. The suspected species of the insect was recorded when possible using key phenotypic differences. The DNA was successfully isolated from twenty-four specimens using the silica method. Then, DNA from the twenty-four specimens was amplified using Ready to Go PCR Beads and the COI Ant primer. PCR products were analyzed using gel electrophoresis, and twenty-four samples yielded bands. These samples were then sent out for sequencing. The sequence samples were uploaded to DNA Subway, trimmed by hand, and analyzed using the Nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTN).

Results:

Out of 24 samples successfully sequenced, 10 were O. fasciatus, 13 were L. turcicus, and one was L. kalmii. All samples had a bit score higher than 1100 and no more than 5 mismatches. The alignment lengths ranged from 622 to 654 bp. Of the O. fasciatus sequenced, 9 were found on a poisonous plant (milkweed) and one was found on a non-poisonous plant. Of the L. turcicus sequenced, 10 were found on a non-poisonous plant and 3 were found on a poisonous plant. All L. kalmii sequenced (1) were found on a poisonous plant. There were three main clades on the phylogenetic tree, all with 100% bootstrap values at the ancestral node: the first clade included the L. turcicus samples, the second included the L. kalmii samples, and the third included the O. fasciatus samples. L. turcicus and L. kalmii are monophyletic, sharing a common Lygaean ancestor. Conversely, O. fasciatus is more distantly related. In the Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation (MUSCLE) alignment, L. turcicus differs the least from the consensus sequence, L. kalmii varies slightly more, and O. fasciatus varies significantly more. O. fasciatus and L. kalmii differ in similar places, although L. kalmii differs at fewer base pairs.

The table displays the results of the DNA sequencing, assigning a species, alignment length, bit

score, and number of mismatches to each sample that was processed.

sequence for each of three identified species. The cicada sequence is the outgroup.

(one for each identified species) and a cicada outgroup.

non-poisonous heliopsis compared to the number of each found on the milkweed plant.

Discussion:

The neighbor joining phylogeny shows three distinct monophyletic clades of seed bugs. As expected, L. turcicus and L. kalmii are monophyletic, sharing a common lygaean ancestor.

Meanwhile, O. fasciatus is less closely related to the other two species, as it is not in the same

genus. The MUSCLE alignment reveals that L. turcicus is most similar to the consensus sequence, with the maximum number of differences between its sequence and the consensus

being 10 base pairs. O. fasciatus differs the most from the consensus, mostly in different places than L. turcicus. L. kalmii tends to vary from the consensus in the same places as O. fasciatus, but the base pair differences are not the same in both species.

The hypothesis that the small and large milkweed bugs would mainly be located on milkweed was confirmed, with 100% of the L. kalmii samples and 90% of the O. fasciatus samples having been collected from this kind of plant. Additionally, around 77% of the L. turcicus samples were found on non-milkweed plants, demonstrating their diet as well.

However, our population predictions were incorrect. The ratio between false and large milkweed bugs was 13:10, and only one L. kalmii was collected. Since the model’s population was so small, can this even be called Batesian mimicry? The mimic would gain no benefits from phenotypic similarities with the model, and the predation on the mimic would only further reduce the population of the model. This raises the question: what kind of mimicry is operating in this habitat, if the classic requirements of Batesian mimicry are not being met? Even though L. kalmii has a negligible population at the sampling site, the coevolution of the Batesian system transfers the traits and benefits of Müllerian mimicry from the Müllerian mimic to the Batesian one. In other words, L. turcicus benefits from sharing the aposematic coloring with O. fasciatus as a result of its mimicry of L. kalmii. Hlaváček et. al (2022) described this system as a Batesian-Müllerian mimicry ring. Among seed bugs it appears to be quite effective, as demonstrated by the large populations of each insect observed in the native plant garden of Randall’s island. Due to the aposematic coloring shared by O. fasciatus and L. kalmii, and the visual characteristics mimicked by L. turcicus, common predators of seed bugs, like birds, avoid them. However, these atypical mimicry dynamics have only been observed on one day, in one habitat on Randalls Island. In order to gain further support for this hypothesized relationship, we would have to sample multiple locations on multiple different days to see if the pattern remained consistent.

References:

DNA Learning Center. “Using DNA Barcodes to Identify and Classify Living Things.” Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. October, 2018.

Duncan, Bill. “False Milkweed Bug.” Ozark Bill, December 30, 2015. https://ozarkbill.com/2015/12/30/false-milkweed-bug/

Heines, Dena. “Guide to Milkweed Bugs (2 Types) Good/Bad? Facts & Photos.” My Monarch Guide, updated December 3, 2024. https://mymonarchguide.com/milkweed-bugs/

Heyworth, Hannah Cecilia. “How Bright and How Nasty: The Economics of Variable Aposematic Traits.” MS thesis., University of Exeter, 2022. ProQuest (30398113).

Hlaváček, Antonín, Klára Daňková, Daniel Benda, Petr Bogusch, Jiří Hadrava. “Batesian-Müllerian mimicry ring around the Oriental hornet (Vespa orientalis).” Journal of Hymenoptera Research 92, (2022): 211-288. https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.92.81380

Missouri Department of Conservation. “Large Milkweed Bug.” Field Guide. 2024.

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/large-milkweed-bug

Missouri Department of Conservation. “Seed Bugs.” Field Guide. 2024.

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/seed-bugs

Missouri Department of Conservation. “Small Milkweed Bug.” Field Guide. 2024.

https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/small-milkweed-bug

Pfennig, David W., Sean P. Mullen. “Mimics without models: causes and consequences of allopatry in Batesian mimicry complexes.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277, (2010): 2577-2585. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.0586

Leave a comment